American Oversight

An informed public,

a strengthened democracy.

Border Wall Investigation Report: No Plans, No Funding, No Timeline, No Wall

Records we’ve obtained, as well as responses from the government saying it does not have documents we’ve requested, show that months into the administration, the agencies that would theoretically oversee implementation of the wall failed to take critical steps including engaging in international advocacy on behalf of the wall, determining a cost estimate or funding source for the wall, securing a construction schedule, making legal preparations to take private border land, and communicating with Native American tribes who live along the border — in sum, showing that the border wall is nothing more than one of the president’s favorite talking points. The absence of records reflecting a serious effort to develop a sound and comprehensive plan to build a border wall suggests that the president’s avowed commitment is simply a rhetorical tool.

The following report uses records obtained by American Oversight — from agencies including the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), its component agency Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the Department of Justice (DOJ), the State Department, and the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) — in conjunction with public audits of the wall by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and Minority staff of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee (HSGAC) to analyze the Trump administration’s failure to make significant progress on building the wall.

Background: Where is the current border fence?

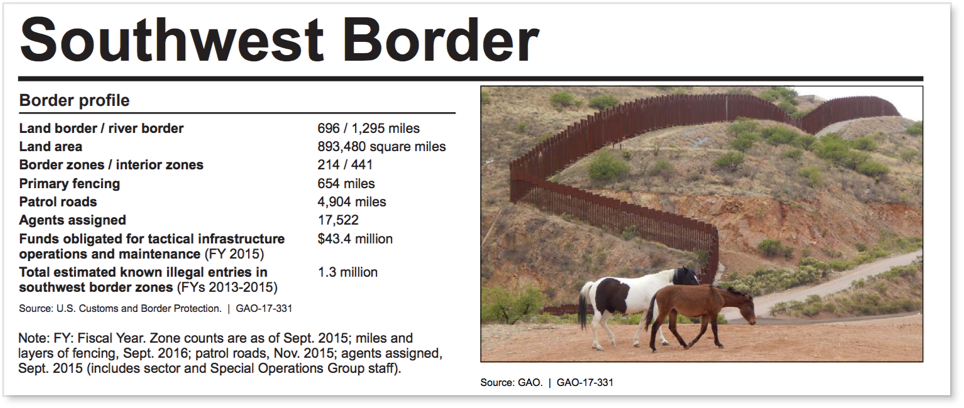

The U.S.-Mexico border is nearly 2,000 miles long. According to 2015 GAO data, 696 of those miles are land border; the remaining 1,295 miles are river border. According to GAO, 654 miles already have primary fencing.

An interactive border map published by the New York Times illustrates where border fence already exists.

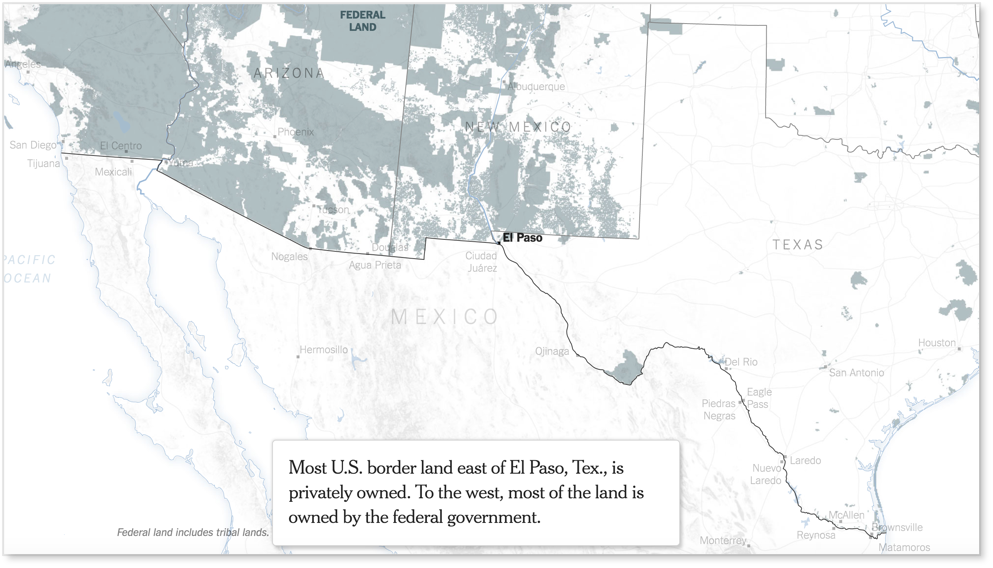

Much of the land without fencing is bordered by the Rio Grande river in Texas. That land is also largely privately owned, as opposed to the federal and tribal lands where there already exists hundreds of miles of fencing. As the New York Times notes, most border land without fence is privately owned.

In order for the Trump administration to build new border wall, it would need to extend the current fence to the east, along the Texas border. However, as public reporting and records obtained by American Oversight show, the administration has made few of the preparations necessary to build a wall.

Top officials placed no emphasis on pushing Mexico to fund the wall

During his 2016 campaign, then-candidate Trump not only used a border wall as a central campaign promise, but also vowed to make Mexico pay for it. The president continues to maintain that Mexico will fund construction of the border wall, despite Mexico’s claim to the contrary.

But State Department records obtained by American Oversight show that during the first months of the administration, officials acknowledged Mexico’s refusal to fund construction of a border wall and did not make it a priority to push Mexico to pay for the wall. In memos created to prepare then–Secretary of State Rex Tillerson for five meetings with top Mexican officials, the State Department consistently referred to construction of a border wall as an issue to address “if raised” — not as a State Department “key objective.”

In a memo for Tillerson’s February 8, 2017, meeting with Mexican Foreign Secretary Luis Videgaray, “key objectives” included managing the bilateral relationship, security cooperation, and migration and border issues. Reference to a border wall appeared in a separate “if raised” section, along with a note that “Mexico opposes the construction [of a border wall], and regards the U.S. requirement that Mexico pay for it as an affront to national dignity.”

The same “if raised” classification of the border wall appeared in briefing memos for four other meetings between Tillerson and Mexican officials: a February 22, 2017, meeting with Videgaray; a February 23, 2017, meeting with Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto; a February 23, 2017, meeting with Mexican Secretary of Government Miguel Angel Osorio Chong; and a February 23, 2017, meeting with Videgaray, Chong, and Mexican Secretary of Finance Jose Antonio Meade.

It wasn’t just the State Department that viewed Mexico’s funding of the border wall as unlikely. Then–DHS Secretary John Kelly attended the February 23, 2017 meeting between Tillerson and Peña Nieto. In a memo for Kelly, “DHS priorities for the meeting” included continued normalizing of the relationship, national security, and economic security. In a separate section titled “issues that President Peña Nieto is likely to raise during the meeting,” the memo noted, “Mexico has shown willingness to review NAFTA while rejecting President Trump’s demands that Mexico pay for a wall the United States plans to build along the border to stop illegal immigration.”

Taken together, these memos indicate that top cabinet officials did not prioritize asking Mexico to pay for the president’s proposed border wall in their meetings with high-ranking Mexican officials.

No cost estimate or funding source

Without Mexico footing the bill for the wall, the Trump administration would need to secure alternate financing if it truly wanted to pursue this massive infrastructure project. But with an incoming Democratic majority in the House of Representatives, it’s unlikely that the next Congress will appropriate funds for a border wall. Public records suggest that not only does the administration not have a funding source secured, they don’t even have a real estimate of how much it would cost to build the wall.

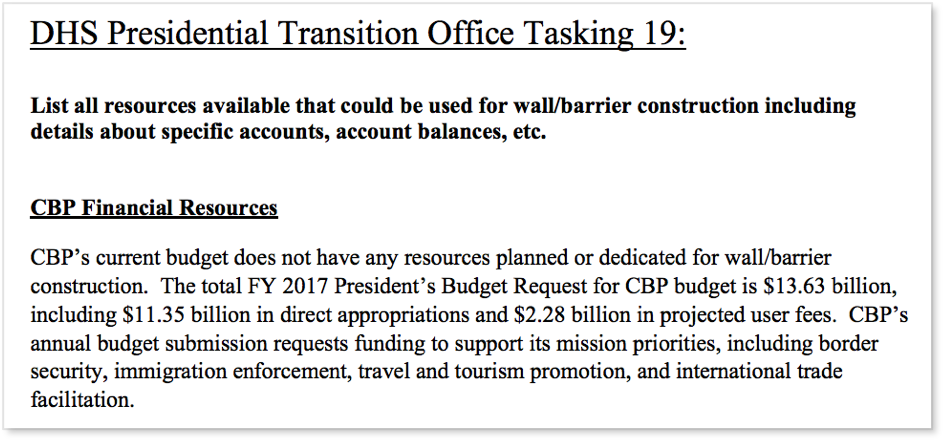

According to records in CBP’s FOIA library, the agency had no funding set aside for a border wall during the transition period. “CBP’s current budget does not have any resources planned or dedicated for wall/barrier construction,” CBP noted in response to a presidential transition tasking request seeking “all resources available that could be used for wall/barrier construction including details about specific accounts, account balances, etc.”

The administration has yet to obtain funding to build a border wall. Earlier this year, Congress appropriated $1.6 billion for border security, but that money is largely for maintenance of current border barriers, not construction of new wall. Congress allocated only $641 million — less than half of the $1.6 billion border security package — to build 33 miles of new fencing, all of which was already authorized by the 2006 Secure Fence Act. The remaining funding is to be used to replace existing fencing and invest in technology.

In November 2018, CBP relied on its $1.6 billion border security package to award a contract to replace “up to 32 miles” of fencing in Arizona, and another two contracts to construct 14 miles of levee wall in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley. The Arizona project is scheduled to start in April 2019, and the Texas construction is slated to begin in February 2019. Though CBP has tried to cast all three contract awards as part of the administration’s effort to build a contiguous border wall, the Arizona project replaces existing fencing, and the Texas contracts allow for construction that has been planned for over a decade. In October 2018, the administration unveiled what it claimed to be the first completed section of the border wall along two miles in southern California. That section of replacement fencing was planned since 2009, though, and was funded with appropriations from fiscal year 2017.

Not only has the president failed to secure funding to construct a wall, but public audits also show that the administration has not even accurately determined how much it would cost to build a wall. The president’s cost estimates of building the wall have trended upwards in recent years. In February 2016, then-candidate Trump said the wall would cost $8 billion. In January 2018, the president claimed it would cost $20 billion. Later that month, the president asked Congress for $25 billion to fund construction of the wall.

An August 2018 GAO report found that the administration had also failed to accurately gauge the cost of a wall. According to GAO, CBP failed to consider how costs would change based on geographical differences — including topography and land ownership — between different possible sites for the wall. As a result, GAO determined that CBP had not accurately assessed the cost-effectiveness of building the wall. And a report published by the Democratic staff of HSGAC in April 2017 found that the full cost of building a border wall could soar to $70 billion. Records obtained by American Oversight show that CBP officials disagreed with HSGAC’s cost estimate, but CBP’s criticism of the Democratic staff’s calculations is withheld under FOIA redaction b(5). That exemption is used to withhold information that agencies consider pre-decisional and deliberative — meaning that CBP did not consider its critical analysis to contain objective facts not subject to the exemption, or to be final.

DHS and CBP records obtained by American Oversight provide additional evidence of the administration’s failure to nail down a funding source or cost of the wall. A thread of emails between CBP and congressional staffers on Capitol Hill show that members of both the executive and legislative branch scrambled to determine where funding would come from soon after President Trump signed an executive order on January 25, 2017 to build the wall.

“I am being asked right now what funds are vurrently [sic] in hand which could be accessed. Need asap,” wrote a Senate Appropriations Committee staffer about available funds in DHS’s budget for border security fencing, infrastructure, and technology (BSFIT). It’s unclear if the staffer received an answer, as the next email in the chain was redacted under FOIA Exemption 5.

A House staffer joined the conversation, noting that “there is a spending plan for those funds so it should have been an easy answer….” A Senate Appropriations staffer, though — possibly the same person who first requested information on available funds — disagreed: “This requiring [sic] a reprogramming request.”

Upon learning of President Trump’s planned executive order to build a wall, another House staffer said, “Apparently, there is a pot of money somewhere we didn’t know about…..and a way to hire people…”

Five months later, the administration still did not know where it might find money to construct the wall. In a slide deck created by CBP and dated June 28, 2017, CBP acknowledged that “[c]urrently, CBP does not have funding to construct border wall operational requirements.”

In the absence of traditional funding sources, some administration officials became creative with ideas to build the wall. Minutes from a DHS sustainability committee meeting in February 2017 show that a Coast Guard official suggested using old ships to build the wall.

At the outset of the administration, CBP did not have resources to build the wall, and it still lacks funding to undertake construction of the wall. With Mexico’s refusal to pay the wall, the administration’s failure to obtain funding through the appropriations process, and an incoming Democratic House majority, it’s increasingly unlikely that the president will be able to find the billions of dollars he would need to construct the wall.

No schedule for construction

The administration has also failed to develop an informed schedule for the substantial infrastructure undertaking of building a complete border wall. The president signed an executive order in January 2017 that called for “the immediate construction of a physical wall on the southern border,” but did not enumerate specifics. In November 2018, CBP awarded contracts to construct up to 46 miles of wall and replacement fencing in Texas and Arizona, with construction reportedly set to begin in February and April 2019, respectively. But nearly two years into the administration, officials have failed to make public a comprehensive schedule for construction of the wall along hundreds of miles of U.S.-Mexico border.

The administration has taken the small step of constructing wall prototypes, but even here the schedule lagged. The prototypes were completed in San Diego in October 2017, but CBP records obtained by American Oversight show that the administration originally planned to complete the prototypes months sooner. The proposed schedule for building the prototypes slipped multiple times. At least one delay seems to have been due to difficulties the administration faced in resolving Buy American Act requirements.

An undated timeline shows that officials initially planned on starting construction on prototypes on June 15, 2017.

Another undated schedule shows that CBP pushed its start date for prototype construction back a week, aiming for June 22, 2017. The revised timeline also shows what may have led to the delay: there were “issues” — labeled with a yellow, instead of green, “status” box — surrounding a suggestion that the Office of General Counsel was supposed to provide the White House on how to resolve problems surrounding the Buy American Act.

A third timeline shows that CBP officials initially planned to complete prototype construction by the end of July 2017.

The various timelines laid out by CBP were ultimately delayed. Prototype construction began in September 2017, and was completed in October 2017 — not in June and July 2017, respectively, as CBP had once planned.

Emails among CBP officials show some of the confusion that accompanied the prototype schedule delays. In March 2017, a San Diego CBP official sent an email to a San Diego County official, among others, noting that “CBP Headquarters released information last evening that prototypes for a border wall are in fact going to be constructed here in San Diego. . . Unfortunately, I don’t have a lot of answers right now.” The email suggests that at least some CBP San Diego officials were not keyed into the administration’s decision to build prototypes in San Diego in the first place.

A July 2017 email from the Assistant Chief Patrol Agent of San Diego’s Border Patrol Sector showed that four months into the process, local officials still lacked key information about the prototype construction. “There is a delay in working through the logistics of construction. I don’t have specific information about what the issue is, but I’m told the plan is still moving forward. Construction may not begin until October.”

In August 2017, some officials were still in the dark about the administration’s prototype plans. An August 1 email to numerous redacted email addresses, after stating that DHS had obtained an environmental waiver in order to build prototypes, noted that “construction is still delayed. We will do our best to keep you informed as information becomes available.”

The administration failed to meet deadlines and keep local officials apprised of prototype construction developments — which represent a small fraction of the planning and coordination that would be necessary to build a contiguous border wall.

Little evidence of legal preparations to take private land

According to GAO estimates in 2015, approximately two thirds of the southwest border is made up of private and state-owned lands. A New York Times map of the U.S.-Mexico border shows that much of the border land east of El Paso, Texas, is privately owned.

In order to build a significant portion of new wall, the administration would need to exercise its right to take private land through eminent domain — and would likely face numerous legal challenges as a result. Any serious attempt by the administration to build a border wall would involve considerations and discussions of eminent domain, and substantial planning for how to address the need to seize a large amount of private land.

Yet in response to FOIAs we filed with DHS and DOJ for records related to eminent domain and the border wall, the records that we received several months into the administration showed no serious effort to plan for a significant eminent domain undertaking. DHS and the United States Attorney’s Offices for the Districts of New Mexico, Arizona, and Southern California produced letters in 2017 indicating the agencies had no records responsive to our requests. While news reports indicate that as of June 2018, the administration had begun preparations to seize private land in the Rio Grande Valley, neither of the U.S. Attorney’s Offices for the two border districts in Texas have responded yet to our March 2017 FOIA request. The responses we’ve received so far would seem to suggest that if efforts are being undertaken to build President Trump’s wall on private land, they did not begin until at least the second year of the administration.

The only records we received in response to our eminent domain FOIA requests were from DOJ headquarters. Those documents consisted of a three-page memo from DOJ land acquisition section officials to environment and natural resource officials summarizing a background conversation between a DOJ lawyer and a reporter, as well as an on-the-record statement that DOJ provided to the reporter. That statement noted that no eminent domain cases had been referred to DOJ as a result of President Trump’s executive order to build the wall.

The administration would inevitably face legal challenges if it tried to seize private land for President Trump’s border wall. In 2008, the George W. Bush administration — in constructing a fence along mostly federal land in Arizona, California, and New Mexico — attempted to seize less than an acre of private land from Eloisa Tamez, a resident of Cameron County, Texas. Tamez challenged the government’s action. It took seven years to resolve the litigation, which ended with the government paying Tamez $56,000 in exchange for the quarter-acre on which the fence sits.

According to an NPR analysis, most of the eminent domain cases over land takings along the U.S.-Mexico border that wound up in court took about three and a half years to resolve. Most of those cases concerned less than an acre of land. President Trump’s proposed wall would require an unprecedented number of land seizures: a USA Today analysis of property records along the Texas border found that almost 5,000 parcels of land could be seized or affected if a wall were built. Construction of a contiguous wall along the border would likely create hundreds, if not thousands, of legal hurdles for the government. The fact that the administration has no records of discussions of eminent domain in relation to President Trump’s wall reinforces the idea that agencies and officials had not started to undertake serious preparations for the wall months into the administration.

Little communication with border tribes

In addition to private individuals, tribal nations control land along the southwestern border. According to GAO’s 2015 estimates, federal and tribal lands make up one third of the border. The Tohono O’odham Nation, a sovereign Native American tribe with members and land on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, controls 62 miles of border land. To make a serious effort to build a border wall, the U.S. government would need to engage with Tohono and other tribal leaders. But according to records obtained by American Oversight, DHS and other agencies made almost no outreach efforts to the Tohono O’odham during the first months of the Trump administration — and the communication that did occur shows tension between the government and the Tohono.

American Oversight sent two FOIA requests to DHS in March 2017 related to tribal land. The first request sought communications with the Tohono O’odham or its representatives. In response, DHS released fewer than 40 pages, about half of which consisted of already-public tribal resolutions and a Senate report. CBP also released records in response to our request, including letters between Tohono Chairman Edward D. Manuel and Tucson CBP officials.

The CBP records show that on March 21, 2017, Manuel sent a letter to Tucson’s chief patrol agent, criticizing CBP’s apparent unwillingness to provide Tohono leaders with details related to the administration’s border security plan. Regarding a March 17, 2017, meeting between Tohono representatives and CBP officials, Manuel said: “Tucson Sector’s unwillingness to provide any details about its implementation of Executive Order 13767 on the Nation is inconsistent with the government-to-government relationship between the Nation and the United States and the requirements of the Consultation Policy.”

Manuel continued: “[W]hen the Nation’s delegation repeatedly asked for details of the Sector’s study and strategy for the Nation’s border during our March 17, 2017 meeting, the Sector declined to provide this information. . . . The Nation cannot provide the ‘input’ that the Consultation Policy calls for without being provided ‘sufficient details’ of Tucson Sector’s border security study on the Nation and the resulting strategy to obtain and maintain complete operational control.”

In a March 22, 2017 response to Manuel, CBP pushed back. “We disagree with your characterization of the meeting,” wrote Tucson’s chief patrol agent. According to the CBP official, “Tucson Sector made no such agreements [about not invoking Section 102, eradicating traditional border crossings, and providing access to state and local law enforcement under 287 (g) agreements] and lacks authority to make any of those promises.” In response to Manuel’s criticism of CBP’s refusal to provide details on a CBP study and strategy, the chief patrol agent stated that “[a]s I stated in our in-person meeting, Tucson Sector is not responsible for this 180-day study, and strategy for the Nation’s border.”

The second tribal-related FOIA request American Oversight submitted to DHS targeted analyses or reports that DHS used to gauge the impact of a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border on sovereign tribal land. DHS sent us a letter stating it had no records responsive to our request as of March 29, 2017.

American Oversight has since received records from CBP in response to our request to DHS, consisting of environmental analyses of border infrastructure projects on tribal land. But DHS’s letter means that more than two months into the Trump administration, DHS leadership had made no serious effort to research the effects of building a wall on land that comprises dozens of miles of the border.

American Oversight also sent a FOIA request to DOJ for any communications with Tohono representatives. In response, we received just 13 pages of records — over half of which were emails among DOJ FOIA officers regarding where to route American Oversight’s FOIA request.

News reports indicate that tension between the administration and the Tohono has persisted since the parties’ March 2017 correspondence. In March 2018, Manuel wrote a letter to Department of Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, criticizing Zinke’s claim that building a wall would increase security. Manuel stated that “the construction of a wall along the Nation’s border will waste taxpayer money,” and that “[t]he Nation also is extremely concerned about the negative impacts a fortified wall will have on our cultural and religious rights, and on our environment.” It’s unclear if Interior ever responded to Manuel’s letter.

“Serious, likely irreparable” environmental damage

None of the records American Oversight obtained through its border wall investigation suggested a serious effort by the administration to build a wall along the entire southwestern border.

Documents we received from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), though, indicate that ecosystems near the border would suffer extreme, irreversible damage if a contiguous wall were built along the border. In 2007, DHS alerted FWS that it planned to build 70 miles of border fence along the southern three counties of the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

FWS southwest regional director Benjamin Tuggle wrote a memo for the FWS director summarizing FWS’s concerns about the proposed fencing. Tuggle noted that “[s]erious, and likely irreparable, wildlife and habitat loss and damage are likely to result from the placement of 70 miles of border fence along the lower Rio Grande Valley NWR.”

Ten years later, in March 2017, an FWS official attached Tuggle’s 2007 analysis in an email to other FWS officials. “Attached are some of the summaries we put together in 2007 when we learned of Border Infrastructure for the first time. Many of the concerns will be the same.”

Additional records obtained by American Oversight show that FWS in 2017 also used assessments from 2012 and 2016 to warn of potential harm that would be caused by CBP’s Integrated Fixed Tower Project (IFT), a system of surveillance towers and networks already in use. FWS relied on its 2016 biological opinion on the effects of the Tactical Infrastructure Maintenance and Repair Program (TIMR) on wildlife to determine the effect of the IFT program. TIMR consisted of “fences and gates, roads and bridges/crossovers, drainage structures and grates, lighting and ancillary power systems, and communication and surveillance tower components.”

The Tohono wanted to confirm that they agreed with the proposals in the biological opinions, which analyzed the effects of TIMR on wildlife.

In response, FWS pointed the Tohono representative to the biological opinions on FWS’s website and attached them to the email. The 2016 biological opinion found that the TIMR project would likely pose a threat to multiple endangered species. TIMR “‘may affect and is likely to adversely affect’ the threatened northern Mexican gartersnake,” the 2016 biological opinion determined.

Additions to the TIMR project in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (OPCNM) would also harm endangered species. “For proposed project additions within OPCNM, CBP determined that the proposed project ‘may affect, and is likely to adversely affect’ the endangered Sonoran pronghorn.”

The harm to the threatened northern Mexican garters and Sonoran pronghorn would come as a result of CBP’s TIMR activities in both species’ habitats. “A total of 130 miles of non-waived roads within northern Mexican gartersnake proposed critical habitat are proposed to be maintained under the TIMR program. . . . In the 2012 biological opinion, about 100 miles of roads were to be maintained within the range of the endangered Sonoran pronghorn; under the current action, this number is increased to 110 miles of roads.”

“Low water crossings,” a type of bridge, would also lead to the threat of harm against endangered species. “[A] total of 65 low water crossings will be maintained within the range of the endangered Sonoran pronghorn.”

Given that FWS in 2017 relied on a 2016 biological opinion to outline the effects of a border security infrastructure program consisting of fences, roads, and towers, it seems that a contiguous border wall — a more invasive security measure than an existent infrastructure program — would raise the same threats to endangered species and ecosystems.

Politics instead of policy

Ultimately, the administration’s confusion and inaction surrounding the wall come as little surprise. Earlier this year, DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen made a sweeping claim at a White House press briefing: “To us, it’s all new wall. If there was a wall before that needs to be replaced, it’s being replaced by new wall. So this is the Trump border wall,” Nielsen stated. In response to a reporter’s clarifying question of whether replacing current wall would count as new wall, Nielsen replied, “Yes, it would.”

If maintenance of current border fence counts as “Trump border wall,” then it makes sense that the administration has not secured funding, a schedule, legal rights to private land, or an understanding with Native American tribes. None of those components are necessary if the Trump administration is not actually building a new wall. Though the president continues to rely on the wall as a rallying cry, the actions — or lack thereof — taken by administration officials and agencies prove that the wall is just that: a toothless demand grounded not in policy considerations, but in the president’s attempt to placate his political base.

American Oversight is continuing to investigate President Trump’s proposed border wall, the separation and detention of immigrant minors, retaliation by federal officials against “sanctuary” cities, and reported attempts to challenge or revoke the citizenship of immigrants who have become naturalized American citizens. Visit AmericanOversight.org to follow these investigations and see all the documents we uncover.

Resources:

- State Department records related to Mexico relations and wall payments: https://www.americanoversight.org/document/state-department-records-regarding-mexico-relations

- DHS records of materials used to prepare former Secretary Kelly for testimony before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee in April 2017: https://www.americanoversight.org/document/dhs-records-related-secretary-kelly-wall

- DHS emails, other records related to the cost and appropriations process for a border wall: https://www.americanoversight.org/document/dhs-communications-about-the-cost-of-and-appropriations-for-a-border-wall

- DHS and CBP communications with border states including Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas about a wall: https://www.americanoversight.org/document/dhs-communications-with-states-about-border-wall

- DHS and CBP emails and outlines of the schedule for border wall construction: https://www.americanoversight.org/document/records-concerning-schedule-border-construction

- DHS communications with the Tohono O’odham regarding a border wall: https://www.americanoversight.org/document/dhs-communications-tohono-oodham-regarding-border-wall

- DOJ communications with the Tohono O’odham regarding a border wall: https://www.americanoversight.org/document/doj-records-of-communications-with-the-tohono-oodham-nation

- FWS documents related to the environmental impact of a border wall: https://www.americanoversight.org/document/fish-wildlife-documents-concerning-environmental-impact-border-wall

- CBP, FWS, and Bureau of Land Management records related to the environmental impact of border maintenance: https://www.americanoversight.org/document/cbp-fws-and-blm-records-on-environmental-impact-of-border-maintenance

See the full report below or download a copy here: