In the Documents: Emails from Fulton County, Georgia, Regarding Election Administration in 2020 and 2021

Emails obtained by American Oversight from Fulton County, Ga., provide insight into the partisan effort to dig up evidence of fraud after the election, and shed light on some of the tension regarding an attempt to oust the county’s elections director.

Former President Trump’s lies about widespread voter fraud and a stolen election not only served his far-reaching attempt to subvert U.S. democracy and remain in power — they also launched a wave of voter-suppression measures and emboldened his supporters to seek out their own “proof” of fraud.

Threats against election officials have also intensified since the 2020 election. During Tuesday’s hearing of the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 insurrection, Shaye Moss, a former election worker in Georgia’s Fulton County gave a harrowing account of the threats she received after Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani falsely accused her and her mother of smuggling in suitcases of ballots to rig the election for Joe Biden.

Fulton County, which is home to Atlanta, was a particular target of election conspiracies, with Biden having won Georgia despite Trump’s pressure campaign on state leaders to reverse the 2020 results. Emails obtained by American Oversight provide insight into the partisan effort to dig up evidence of fraud after the election, and shed light on some of the tension in early 2021 regarding an attempt to oust the county’s elections director.

Poll Watchers

In the weeks after the 2020 presidential election, Trump and his allies were focused on the illegal ploy to overturn his loss. As they continued to push false allegations about widespread voter fraud — including baseless claims about the dangers of absentee voting and ballot drop boxes — those lies infused the lead-up to the Jan. 5, 2021, runoff elections in Georgia for two U.S. Senate seats. At the time, election workers in the state, as Politico reported in December 2020, were “stressed and fatigued” from dealing with “bizarre conspiracy theories, ballooning costs and coronavirus-related staffing problems” — and even vigilante poll watchers.

Emails American Oversight obtained from Fulton County provide a glimpse of this conspiracy-tinged atmosphere of distrust. In a Dec. 19 email to poll watchers, the county’s Republican Party vice chair, Betsy Kramer, said that she had been sent “a couple of photos” of cars with out-of-state tags parked at an early-voting location. Kramer directed the poll watchers to take photos of any out-of-state cars at voting sites and to avoid answering directly if questioned about what they were doing.

“While you are poll watching, go outside a few times during your assignment and look around the parking lot,” Kramer wrote. “If someone asks what you are doing, say you are stretching your legs.”

Kramer also told poll watchers to record videos of voters dropping off their ballots and to send the videos to a GOP email address for voter fraud reports. Those who weren’t assigned to early-voting locations “need to stake out the absentee ballot voter drop off boxes,” Kramer wrote. “Be especially aware of anyone dropping off more than one ballot.”

Kramer’s instructions were forwarded to a reporter by Fulton County’s elections director, who wrote that it had “caused confrontation at Adams Park Library today.” The director, Richard Barron, also forwarded Kramer’s email to members of the county’s Board of Elections and to the Georgia secretary of state’s chief investigator, Frances Watson. (Watson was the recipient of the infamous Dec. 23 phone call from Trump — a recording of which was obtained by American Oversight — in which he asked Watson to do “whatever you can” to help him win Georgia.)

In emails exchanged later that month, county election workers alleged that some poll watchers had violated rules. On Dec. 28, a county employee wrote that three Republican Party poll watchers were at a polling location and refused to leave despite rules permitting only two watchers from the same party to serve at the same time. The email was forwarded to the county’s party chair Trey Kelly, who asked one of the poll watchers about the accusation. The poll watcher denied breaking the rules, pointed out other alleged issues at the polling site, and added, “There was fraud committed in this election and Biden did not win.”

Another poll watcher replied to the email thread, alleging that a manager at the polling location had told her all voided absentee ballots would be shredded — adding, “I think she said at the warehouse?” — and calling on elected officials to address such “fraudulent actions.” State Sen. John Albers forwarded the complaint to an official in the secretary of state’s office, who forwarded it to Watson.

The email was also shared with multiple other officials, including the county’s deputy elections chief, who wrote that the alleged incident was currently under investigation by the secretary of state’s office. “Those same poll watcher[s] also claim that Ocee Library has been shredding ballot[s] with their shredder,” she added. “Which is an untruth.”

Fulton County Elections Leadership

In the weeks surrounding the presidential election and the January Senate runoffs, Fulton County election workers were subject to intense scrutiny and even death threats from supporters of Trump’s stolen-election lies. Barron, the county’s elections director who had been in the position since 2013, was the target of many such attacks.

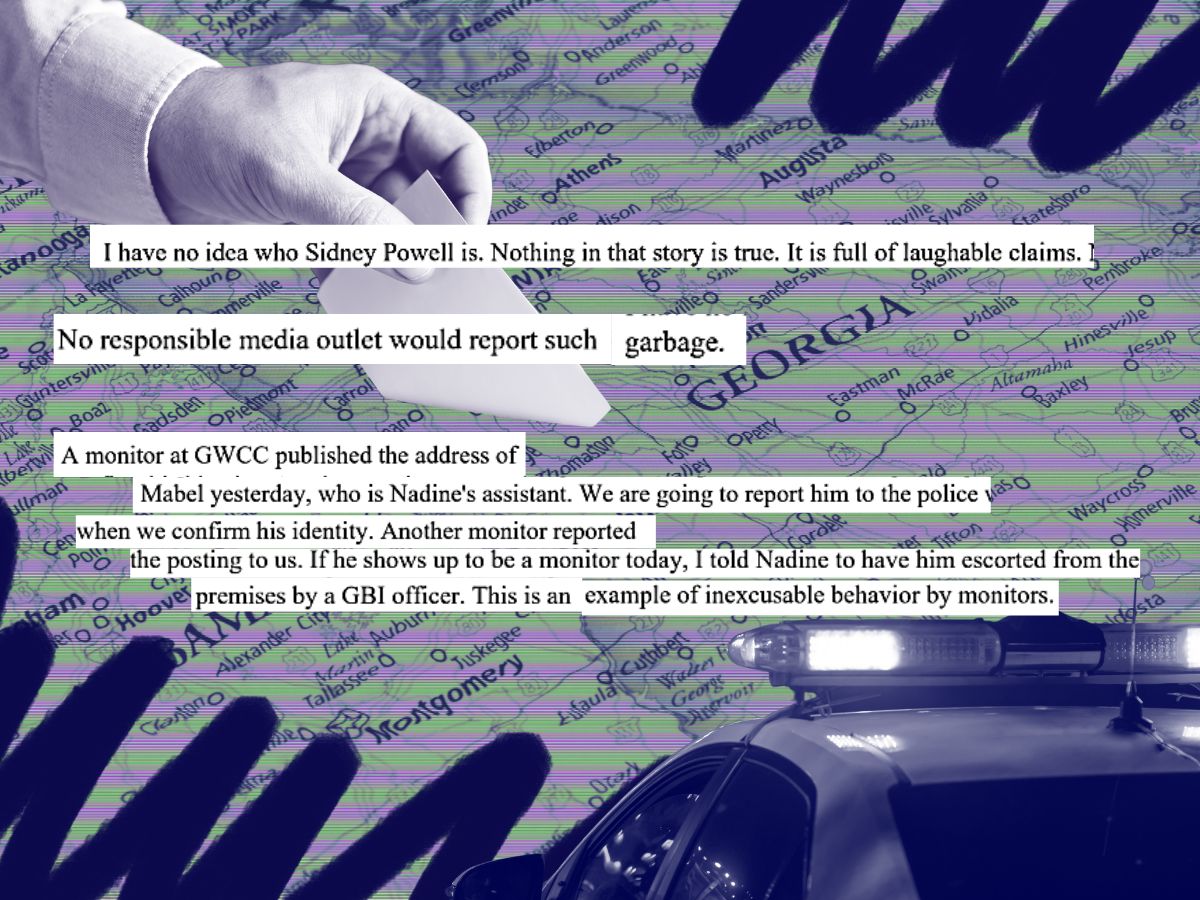

On Dec. 1, Barron responded to an email from Fulton County Board of Elections member Mark Wingate, who had sent Barron an article from a conservative publication. The article discussed an allegation by Sidney Powell, a Trump-allied lawyer who pushed Trump’s outlandish fraud claims, that the county had tampered with voting machines. Barron criticized Powell for “contributing to the atmosphere that is causing us to get threats.”

“Nothing in that story is true,” Barron wrote. “It is full of laughable claims.” Barron added that the day before, a poll monitor had published the address of a county elections employee’s assistant, which Barron called “inexcusable behavior.” A month later, on Jan. 13, Barron replied to a voter who had asked about Powell’s accusations against the county, writing, “Sidney Powell has been discredited widely.”

The county had faced challenges in the June 2020 primary, including excessively long lines and an overwhelmed mail-in voting system. In early 2021, Barron survived a vote by the Fulton County Board of Elections to oust him from his position over criticism of that election. He later resigned from his position the day after the November 2021 local elections, officially leaving in April 2022 after having been for months subject to relentless, Trump-led attacks.

American Oversight obtained emails related to the election board’s vote, which took place in February 2021, when members voted 3–2 behind closed doors to dismiss Barron — a decision that was ultimately overturned by the county’s board of commissioners.

On March 3, Commissioner Natalie Hall sent an email to a list of state legislators and nonprofit leaders, accusing Commissioner Bob Ellis of having proposed a resolution that would be a “back door tactic” to still fire Barron. According to Hall’s email, Ellis’ resolution would limit the commissioners’ power to decide the appointment or termination of the elections director.

In an email sent the day before, Ellis replied to a voter who urged him not to fire Barron and criticized new legislation that would make voting harder. Ellis said that he would be “voting to uphold the decision of the Board of Elections” and “not politically inserting myself in the Elections process.” The resolution was pushed back during multiple subsequent board meetings and did not pass.

In February 2021, the Fulton County district attorney launched a criminal investigation into Trump’s attempt to overturn the election results in Georgia, and a grand jury was selected in May of this year.

American Oversight obtained these records in response to an open records request and continues to investigate threats to democracy and voting rights in Georgia. Last year, American Oversight obtained records revealing county officials’ reactions to legislative efforts to restructure election boards throughout the state. In November 2021, we reached a landmark settlement with the secretary of state’s office that will enhance public access to government records.